We’ve each talked a bit about how we got started on gaming – but there are four of us, and this month has five mondays, so we decided to leave the best for last: The prologue of Artemis Games – the story of our first games together.

We met at Vague – The MMU tabletop gaming society – despite the fact that none of us had ever attended MMU, nor had any intention of doing so. I was, at the time, studying Physics at University of Manchester, while Amy was studying Biology at Salford University, and both Loz and Ali had finished their university careers already.

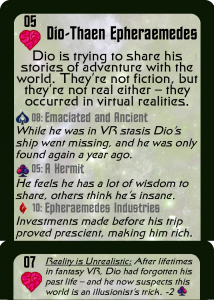

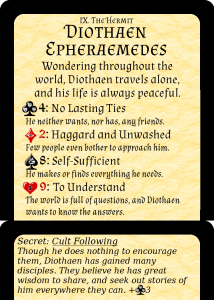

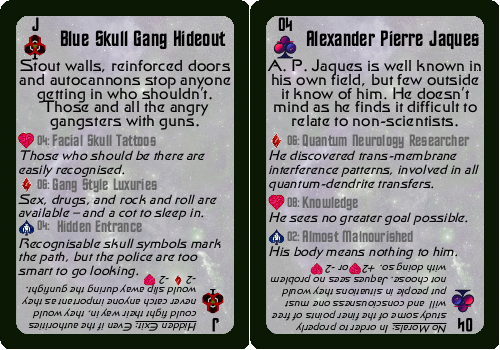

We were largely brought together by a friend who (though not part of the business) remains part of our gaming group – Iain Fortune, who appears in our Concept Cards as “Iain The Fortunate – creator of the Pot of Endless Tea”. Me, Loz and Iain played a brief D&D 4th Edition campaign at Vague, and then Loz mentioned that their gaming group was down a player – and as it happened we lived just down the street from them, so me and Amy ended up joining Loz, Ali, Iain and their friend Shiny in a new campaign at their house.

After the first two stories in this campaign we decided to sit down together and build a world for it – Twissen, a cylindrical world orbited by two suns (one northern, the other southern) and a single moon – and one where the gods themselves were all mad.

This campaign lasted for several years but as we’re talking origins, I might as well finish this up by explaining the its origin story:

The Beginning

The world was created when the Elemental Chaos, substance without form or order, collided with the Divine Prism, form and order without substance. The center of this collision became the mortal world, but the impact was felt throughout both realms – suddenly the Elemental Chaos had minds capable of shaping their surroundings, and the infinite minds of the Divine Prism had matter on which they could act. The northern end of the cylindrical world fell off into the Divine Prism, while the southern end sank into the Elemental Chaos.

This new-formed world had a sun, Shamedan, born of the elemental fire which burnt the southern lands, and a moon, Procan, born of elemental water which brought rain and tides to the southern lands.

Shortly thereafter gods, elementals and nature spirits formed – each within their own realm. The elementals cared little for the oddity that was the mortal world, while the nature spirits were born of it and could not leave, but the gods saw it as a toy with which to play – matter to shape to their whim.

It is at this point that the world gained its northern sun, Pelor, and its northern moon, Sehanine, as gods reached into the world. The sun was born of pure radiance, and the moon of condensed thought.

Intelligent mortal life appeared from nature – the dwarves from the soil, the dryads from the trees, and the merrow from the sea itself. Each lived in harmony with their element, drawing from it just as any other animal would, and returning to it with their death.

Three gods, seeing these new forms of life, decided to create their own immortal races: Amat created the dragons to rule over all; Corellon created the fey to experience the world; Io created the deva to explore and learn.

The dragons started the war of worlds by attempting to conquer the Elemental Chaos – leading to that chaos striking back against the gods, with the mortal world stuck in the crossfire. Amat was slain – split in twain to become Tiamat and Bahamat, the two dragon gods – but the war raged on.

Unable to endure this war the spirits of nature waited for an opportunity – the Grand Conjunction when the elemental and divine realms were closest to mortality – and struck against the gods, using two great weapons:

The first was born of Mawra, spirit of predators, and was a great beast of indestructible power – known as the Tarrasque – which sought to consume all beings of divinity.

The second and greater of the two was born of Nurgle, a spirit of pestilence, and became known as The God’s Plague. This pestilence was carried to the Elementals by Nurgle, and to the gods by Mawra.

The God’s Plague spread through both sides of the war, infecting their essence and driving them to peculiar insanities. The southern sun and moon were first to show the effects – Shamedan’s heat grew, burning the southlands ever more intensely, while Procan first reached upwards, then threw himself into the ocean while ranting about the powers beyond the stars.

Eventually all the gods, and all their immortal children, would grow equally insane, and so Corellon and Io sought to save their people by pulling from them their sparks of divinity.

The Fey

Corellon first attempted to save his people by isolating them – pulling them into their own dreams so that their divine sparks could be safe. In doing so he created a whole new realm of reality, the land of Fairy, a dreamlike mirror of the mortal realm. But while he succeeded in creating a new world he realised that he himself was infected – and that this infection would spread regardless of his actions. Thus he changed his plans – pulling the divine sparks from almost all the fey, concentrating it into the lords of the fey courts whose job it became to dream Fairyland into existence.

The fey he had pulled into Fairyland became split among the “high elves”, or eladrin, who maintained their separation from the dream and held themselves tall through pride, and the gnomes who became part of the dream, made of illusions and fragments of the nature around them.

The fey left in the mortal realm had many different fates. Some lived in the forests of the central lands, and those became the “wood elves”, living in concert with and as part of nature; but most lived in the southlands and were faced with death beneath the burning sun. More than half died within the first few weeks of becoming mortal, but the rest found themselves forced to choose a path. Some changed themselves to be as harsh as the desert, becoming the desert hags, a race known for their worship of fire; others copied the snakes and crawled beneath the sands to live, becoming known as the “dark elves” or drow; a third group chose to dive into the oceans, becoming the first merfolk; and a fourth chose a darker path – they sought to follow the souls of their dead friends, and found themselves in a new mirror of the world, the Shadowfell, created as a place for immortal souls to go after death – these became the “shadow elves” or shadar-kai.

The Deva

Io reacted more slowly to the threat, having first to study its nature, but once she did she began systematically extracting the divinity from her children. The majority of deva became humans, a simple race that possessed a thirst for knowledge beyond most others.

Some of the deva however had been in different forms when their sparks were removed – and those found themselves stuck with their transformation. Those in mammal forms became the bestials, capable of changing from animal form to beastmen though not fully back into a “civilized” form, but those who had taken non-mammal forms were permanently stuck in a hybrid form, losing most of their intellect in the process as they became Harpies, Lizardmen and other such monstrous humanoids.

Io’s delayed action meant that a whole city of his people kept their spark too long, and became infected with the plague. These became the rakshasa, a dangerously amoral immortal race that would do anything for knowledge – no matter who might be hurt – and experimented on every other race.

The Dragons

With Amat dead, and Tiamat and Bahamat still reeling, there was no-one to pull the spark from the dragons – leading to them all becoming crazed with their megalomania, and most of them dying in battle with one another. Their children, the dragonborn who had been created for them to rule, became their successors, running the dragon-cities as they always had just without the dragons lording over them.

The Greenskins

When Procan entered the ocean, he brought with him change and monstrous entities, serving as a portal to a realm that should not be. Many of the merrow sought to flee the corrupted ocean – and so they did. Most fled on to land and islands, becoming the orcs – a race of pirates and sailors known for raiding the coastal lands – but some found themselves pulled through the portal, and became known as the gith, green skinned warriors that could swim through the void as though it were water, with minds attuned to the impossible.

And with that, the second age of the world began – a world where immortal and mortal races collided, and crazed gods begat even more crazed devils.

Please follow and like us: