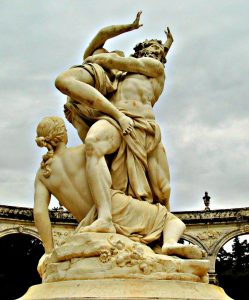

L’Enlèvement de Proserpine par Pluton, Sculpture by François Girardon; photograph by Evan Lawrence Bench, used under CC-SA

Hades is King of the Underworld, and brother to Zeus and Poseidon. Although in popular literature he’s been painted as a Bad Guy, the Greeks didn’t see him as evil – more as a part of Nature. He was worshipped as both the Lord of Death, and as giver of the wealth of the earth – miners and smelters revered him as Master of Metal.

We might imagine that sacrifices to him would be a dark act, but the Greeks – and Romans, worshipping him as Dis or Pluto – saw nothing wrong in feeding the god with the smoke of animals. In most myths, he is portrayed as vicious, but not really cruel – merely a product of his nature.

Cerberus -The Three-headed Hound at the Gates of Hell – translates as “spotted”. So, Hades named his dog “Spot” (a fact that has become much better known since Jim Butcher used the idea in Skin Game, one of his Dresden novels)

Story of the God – The Reluctant Bride

Persephone, the young daughter of Demeter, was picking flowers in a field with her friends and playmates, the Oceanids. From a nearby cave, up out of the earth, came the fearsome Hades, Lord of the Underworld, riding a chariot drawn by two giant dogs.

He was immediately smitten by her beauty, and attempted to carry her off to his realm to wed her. She screamed, but there was no-one who could hear and come to her aid. So Hades dragged her beneath the earth to his palace, and set guards about her, so that no-one else could come near her.

When her daughter did not come home, Demeter left her place on Mount Olympus and came to earth. She searched throughout the world, neglecting her work which was to make crops grow and cattle breed. Eventually, she found one of the Oceanids hiding and crying. When Demeter heard where her daughter was, she went to Persephone’s father, Zeus, and begged him to intercede with their brother Hades for Persephone’s freedom.

“I can only free her if she has taken no food. If she has eaten in the Land of the Dead, she has become a part of it, and even I cannot overcome the will of the Fates” said Zeus

They descended to Hades court, only to discover that Persephone had that day eaten six pomegranate seeds from the orchard outside Hades’s palace. As she had not eaten a true meal, but only part thereof, Zeus and Hades agreed that Persephone could split her time between the realms of the living and the dead, thus mollifying Demeter so that the earth would be made fruitful again, .

So, now Persephone spends six months of the year with her grim husband – one for each seed -, and six months in the light with her mother. In the Spring, she still plays and dances in the meadows, and where her footsteps fall, flowers grow.

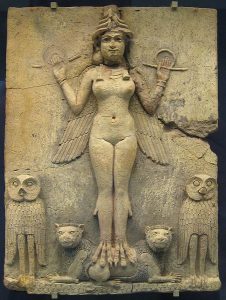

The parallels between this story and Ereshkigal’s tale are interesting – both explain Summer and Winter through the kidnapping of a loved one by the god of the underworld. Whether the tale of Persephone is descended from that tale remains an open question.

In your Games and Stories

Hades is the Lord of the Underworld – the land from which riches come. His grandest temples will be filled with monstrous guardians – but might well be worth an adventurers time for the vast wealth such creatures might guard, or the possibility of recovering a loved one.

As the richest god, with a known love for music (as seen in the tale of Orpheus) Hades might be the patron of bards and entertainers. He is also a suitable deity for merchants and nobles, who keep his gold and trade his silver.

Hades has a debatable relationship with undead. On the one hand, the dead belong in his realm and he is loathe to let them go without recompense. On the other, some undead might be his subjects – even his agents – in the mortal realm. You’ll have to decide whether he loves or hates the vampires and liches of your world – and whether his wife agrees with him.

Persephone’s cycle of death and rebirth might also allow some kindred souls to travel with her, resulting in a form of resurrection that only allows the recipient to remain alive for the length of the summer – a temporary respite, but perhaps long enough for one last epic adventure.

For more help building fantasy worlds, buy us a cup of tea at the Jigsaw Fantasy Patreon!