Emperor’s Hand is a young game, born this very year. Speaking as someone who’s been working on the same (unreleased) game for over half a decade, that’s a very quick turnaround.

The game is in some ways finished, but in other ways not. The deepest problem with it is that it only truly works in the 3-5 player range, a rather

So, here’s a run-through of how the game came to be. You may want to take a look at the print and play to fully understand the details described.

The Spark of Inspiration

The simple answer to “what inspired this game?” is this contest on TheGameCrafter (which we didn’t enter due to the unfinished state of the game’s artwork) and its linked video on Trick-Taking mechanics, but without context that doesn’t really give the right idea of what happened.

To me, inspiration is about a spark that starts a fire burning inside my mind, illuminating a new idea – It’s a single moment of thought that grows into something more – but it is nothing without fuel.

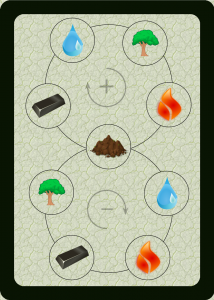

In this case the fuel was something I’d been pondering for a while – the Wu Xing and the way it connects the five elements in a pair of cycles, perfect for tie-breaking or creating a set of mystical relationships.

That interest came partly from looking at the number of clones of Magic, including some that cloned it all the way down to the colour pie. But that’s another story.

So, the spark landed in potent fuel – what about using the asymmetric relationships to make a trick-taking game where the trump was neither constant nor changing, but was found in the relationship between the suits?

Designing the Game

The inspiration in place, the game was still somewhat empty – it was a simple rock-paper-scissors-lizard-spock scenario, a single mechanic, along with a strong theme.

So I started to delve a little deeper into the theme – yes, every element can be said to trump two of the others (the one that creates it, and the one it destroys) but those two relationships are fundamentally different, and a good game could reflect that fact.

That’s where the idea of having positive and negative elemental modifiers on each card came into play. The first thought that followed this was that it could, potentially, be used so that every card had a unique combination of modifiers (from +5/-0 to +0/-5) ensuring that no card was always superior to any other card – but this resulted in the modifiers having an overwhelming impact, so we decided to go with the simplified +3/-0 to +0/-3 that the cards now have – accepting that a few cards would be strictly superior to their neighbours.

With that in place we had a playable, and somewhat fun, game simply by going round the table playing cards in turns. But it wasn’t great – it was mediocre. So we started looking for ways to improve it, making it both more tactical and (vitally) more fun.

The quickest way to find new tricks for a game is to look at old designs, whether your own or others, and draw from them. If possible, looking for solutions that were both:

1) Aimed at the same problem; &

2) Successful in solving it.

In the case of Emperor’s Hand the most immediate problem was Kingmaking – the last person to play in each hand was the most likely to win, but they always knew whether or not they would win, and if they couldn’t (due to not having the right card) they weren’t just throwing away a worthless card – the modifiers from their card could well tip the balance between the other players, deciding who won. Not a fun situation to be in.

This was a new problem for us – but it belonged to a broader category of problems: People who play later knowing too much. That broader category has a common solution that can almost always be applied in card games – simultaneous (face-down) play – so we applied that solution…

We didn’t even need to playtest the face-down play to realise that it caused a big problem in turn; it removed all the information, meaning that every round the starting environment was identical, with nothing to inform the choice. We needed something to differentiate one round from the next, an element in play before the face-down stage, and there were two elegant ways to do that:

1) Reveal and discard the top card of the deck each round, counting that card’s element as being in play; or

2) Have one of the players play face up, and then the rest play face down – so there’s a first player but no last player.

We’d used the first option before, and it worked, but it didn’t feel quite right for this game, so I decided to try option 2 and, in order to kill two birds with one stone, I made the player who played face up be the player who won the previous hand – thereby making it less likely to have overwhelming victories, even when there’s a significant skill gap.

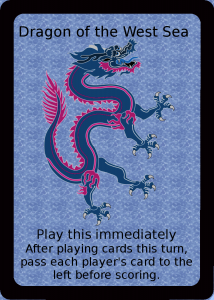

The last decision we made purely in what I think of as the design phase was creating the dragons. The dragons were a way to add further variety to the game, without significantly increasing the complexity – and they are effectively free in terms of printing costs. 1)A Note on Numbers

Throughout the design process, we often looked at the possibility of using an 88 card deck, due to the positive associations of that number in Chinese culture. It may seem odd, therefore, that we eventually settled on a 54 card deck, as 4 is an unlucky number connected with death. While in part this number of cards was a sacrifice to practicality (88 would be more apt, but it required complicating the game) we did take a look at the aesthetic meanings – while 4 itself is unlucky, 54 isn’t, because 5 has a connection with “no”, making 54 “no death” – not always a good thing, but rarely a bad one

The design on the dragons took a few steps – we had four cards to work with, so using the four cardinal directions (North, South, East and West) seemed obvious, and they correspond neatly to Up, Down, Right and Left. Up and down were trivial – doubling the bonuses and penalties from the elements makes for a significant departure of tactics while accentuating (rather than damaging) the core gameplay.

Right and Left also had immediate connections – the player’s to your right and left – but those were less easily applied. We started with the principle that the cards should never cancel out, so the two had to interact with your neighbours in different ways. Passing cards wasn’t a huge leap, though the first draft passed the cards whole hand – which proved to be somewhat meaningless, so we switched to passing a single card. Playing for another player on the other hand was something unusual, but it’s a trick that often works – making players play to lose is often a fun twist.

There’s much more to the game – and still more changes to come before the final version – but these are the elements that I’d count as the original design. I’ll talk about the changes since then later.

Next week, however, will be talking about Jigsaw Fantasy

Until then, Be Well

-Ste

References

| 1. | ↑ | A Note on Numbers

Throughout the design process, we often looked at the possibility of using an 88 card deck, due to the positive associations of that number in Chinese culture. It may seem odd, therefore, that we eventually settled on a 54 card deck, as 4 is an unlucky number connected with death. While in part this number of cards was a sacrifice to practicality (88 would be more apt, but it required complicating the game) we did take a look at the aesthetic meanings – while 4 itself is unlucky, 54 isn’t, because 5 has a connection with “no”, making 54 “no death” – not always a good thing, but rarely a bad one |