E is for Ereshkagel – Mythic Mondays

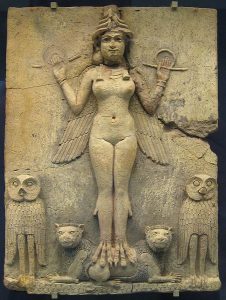

The Burney Relief is believed to display either Ereshkigal or Ishtar. Photograph by Babelstone

Moving away from the more familiar gods, this week we’re exploring Sumeria – and more generally the ancient Mesopotamian mythology. Most mythologists don’t make a clear distinction between the Mesopotamian cultures – that is, the dozen or so cultures that ruled much of the area now known as the Middle East (approximately Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Syria and Israel) – as their religions all share clear developmental relationships.

From at least 3500 BC (their earliest known writing) until about 50 BC (when the Romans advanced into the province) there were a whole string of empires – the Hittites, the Babylonians, the Sumerians and the Persians. From our point of view, they can be considered together just as the Greeks and Romans can, because they broadly shared a pantheon. Looking from one to another you might find that Ishtar becomes Inanna or Astarte – but the powerful female fertility deity is similar throughout.

The Sumerians feared their gods – rather than the kindly parent figures of Classical myth, or the very human Norse pantheon, the Sumerian Gods are chthonic forces of nature, and most often of water – for people living on desert flood-plains water is by far the most important part of nature.

At the core of the pantheon is one family – a father, Ea, god of sweet water; and two sisters. Ishtar rules life and fertility, and Ereshkigal rules death and winter. Their story is a take on the winter tale.

The version I present is but one of many translations – very little record has survived the millennia, and thus the story as I tell it will inevitably differ from any of the versions that the Sumerians wrote.

Story of the God – The Waters of Life

Ereshkigal, Queen of the Great Earth, was alone and in mourning. Her husband Gugulanna, The Wild Bull of Heaven, was gone from the world.

Her sister meanwhile was happily celebrating her life, and courting a new lover named Tammuz (god of food and vegetation).

Ereshkigal was angry that Ishtar would not share her mourning – and so she captured Ishtar’s lover and trapped him in the Underworld. Ishtar would not let this affront stand, and thus she approached the gates of the underworld and demanded that the gatekeeper open them, threatening to burst them open, so that all the dead would be loosed on Earth.

As Queen of the Underworld Ereshkigal could not risk her domain being destroyed, and so she ordered that Ishtar be let in, but only “according to the ancient decree”.

The gatekeeper let Ishtar into the underworld, opening one gate at a time. At each gate, Ishtar was required to shed part of her jewelry and clothing. When she finally passed the seventh gate, she was naked.

Ishtar spoke then with her sister, asking her to release Tammuz from death, but Ereshkigal refused. Enraged, Ishtar threw herself at Ereshkigal, and so Ereshkigal ordered her servant Namtar to imprison Ishtar and unleash sixty diseases against her.

With Ishtar imprisoned in the underworld all fruitful activity ceased on earth. When the king of the gods, Ea, heard of this, he created a being called Asu-shu and sent it to Ereshkigal, telling it to invoke “the name of the great gods” against her and to demand the bag containing the waters of life.

Ereshkigal was enraged when she heard Asu-shu’s demand, but she had to give it the water of life. Asu-shu sprinkled Ishtar with this water, reviving her. Then Ishtar demanded Tammuz as payment for her time. Ereshkigal refused – as Tammuz was dead he could not be allowed to leave – but Asu-shu suggested a compromise: Tammuz and Ishtar could share their life, spending half of each year together among the dead, and the other half together among the living.

Thus it came that they passed back through the seven gates, getting one article of clothing back at each gate, and were fully clothed as they exited the last gate.

In your Games and Stories

From Narnia to Anne Rice, we’ve had a lot of Evil Winter Queens, and Ereshkigal is the grandmammy of them all. As herself, she makes an epic implacable adversary. Give her powers over cold and control over death, perhaps the ability to return revenants, and you can make her a good old fashioned out-to-rule-the-world villain

As a patron, she grants the power to both enter and return from her realm. Liches and necromancers might sacrifice to her to replace their own souls with that of others. This is reminiscent of the Dark Eldar of Warhammer 40K, who sacrifice souls to She Who Thirsts, lest She quench her thirst on the Eldar. This plays to her unknowability – beyond the gate of death.

As a winter deity, it is possible that she is a necessary part of a greater cycle. The oak seed sleeps under the snow, and the quenching of the heat of summer (see Shamadan in Concept Cards – Epic Characters for the evil desert sun) – D&D’s Raven Queen is an example of this kind of beneficent winter deity.

Winter need not be evil, merely hard and testing. For examples of these kind of winter spirits, some of Empire LRP’s Eternals display this aspect of Winter – the trial to temper the quester against greater challenges.

Really enjoying Mythic Mondays. Lots of interesting stories and ideas for taking them into games. Looking forward to the rest of the alphabet!!!! Mary Wellington New Zealand

Pingback: H is for Hades - Mythic Mondays